The inner street. Words couldn’t be more concrete, entirely in line with the architectural vision of the desired Utopia, the Bijlmer. The inner street, a public walkway on the first floor that connected both residential blocks of the apartment complex, conceived as a bustling promenade full of entertainment. Ultimately, there couldn’t have been a greater contrast.

Where no grass grew, we found beauty in potential. On rainy days, we spent hours in the long empty corridors of concrete, steel, and glass. Everything was explored. The mailboxes, resembling miniature metal flats, stood on legs and had pointed roofs. Since nothing was pointed in our surroundings except the neighbor’s teeth, this sparked our imagination. They were like safes filled with gold coins from a pirate movie to us, and we read each other the names on the mailboxes to fantasize about their lives and origins. Sometimes, we came across a name we knew from school or the neighborhood.

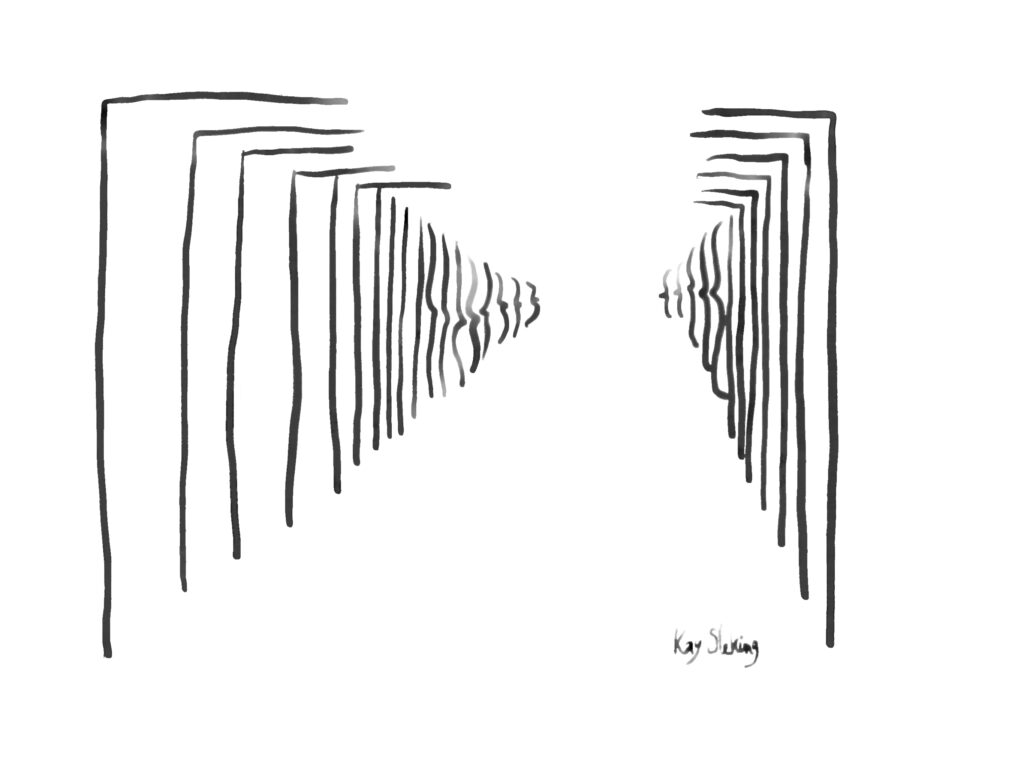

Further down the inner street stood a large wooden artwork, a kind of letterbox you could see through. Because we had no idea why it was there and what purpose it served, it gave us a serene kind of fascination. Very different from the large waste disposal areas with wheeled containers, hidden behind swinging doors emitting an intense smell.

The letterbox had a scent and gleamed, and we hid our found treasures in it, along with notes written to each other in secret code. Every once in a while, the letterbox would be cleaned, and then we’d lose everything. As children, we could let our imaginations run wild in the inner street.

In the evening, the brightly lit and deserted inner street became a catwalk for prey.